a reflection on the end of an era

Yesterday I handed in my last assignments for my last course in my Master of Educational Technology degree through the University of British Columbia. While I won’t graduate until May, it marks the end of an era – just shy of six years I have been plucking away at courses through UBC, first with my post-Bacc in Teacher-Librarianship, and then this program. Honestly, it probably won’t sink in until this January when the next semester begins and I am not juggling the demands of my day job and academia (and supervising the Varsity Boys Volleyball team, haha).

I am thankful for the learning of these years; the ideas and architecture of teaching, learning, and technology that have been made visible through thinkers and makers with skill much greater than my own. At least once a week I am reminded of the meme posted below, and when I pull back from my own unique situation, lenses, and experiences, I continue to be humbled by all of the things I know I don’t know, and even more so the things that I don’t know that I don’t know.

One thing I wish I’d had throughout this degree — and especially in the final projects — was a small community of co-designers. Working full-time while studying part-time often meant creating in isolation or across time zones and distance, without the iterative conversations that sharpen ideas and reveal blind spots. Learning is ecological, and I felt the absence of that ecology at times. For anyone thinking about MET, I strongly encourage it, but especially for you to take the financial hit and take as many summer institute classes as you can. It was these experiences that really got me keen on the importance of hybridity. Even so, the work felt like a reminder that none of us should be designing the futures of education alone.

The more I learned, the more I realized that technology is never neutral — it always arrives embedded with assumptions, values, and power. I came into this program as a tech optimist, but leave it as a tech realist. This kind of program (both the T-L one and the Ed Tech one), would not have been possible to me given my geographic location. Such programs don’t exist here in Manitoba. This program was a gift — but one that came wrapped inside an increasingly precarious technological landscape. However, to borrow from the words of Cory Doctorow, the enshittification of technology has hollowed out some of my previous optimism. When so much of the truly equitizing and democratizing potential of technology is hidden behind paywalls and gradually whittled away even then for increasing add-ons you begin to wonder if the world-views of yourself and the architects of these applications are in alignment.

As a teacher-librarian trying to think carefully about ed tech, I see the role of libraries, both public, elementary/secondary school, and university as a solution to some of these challenges. This will require sustained public funding, and the (mostly) corporations that design these materials to subsidize access to ensure these technologies don’t become yet another divide between the have and have nots. It is not hard to imagine a future where the ability to participate in digital culture depends entirely on one’s ability to pay for the tools required to access it. Perhaps this is no different than inequities within print culture — but it still runs counter to the vision of education I was raised in, both as a student and later as a teacher.

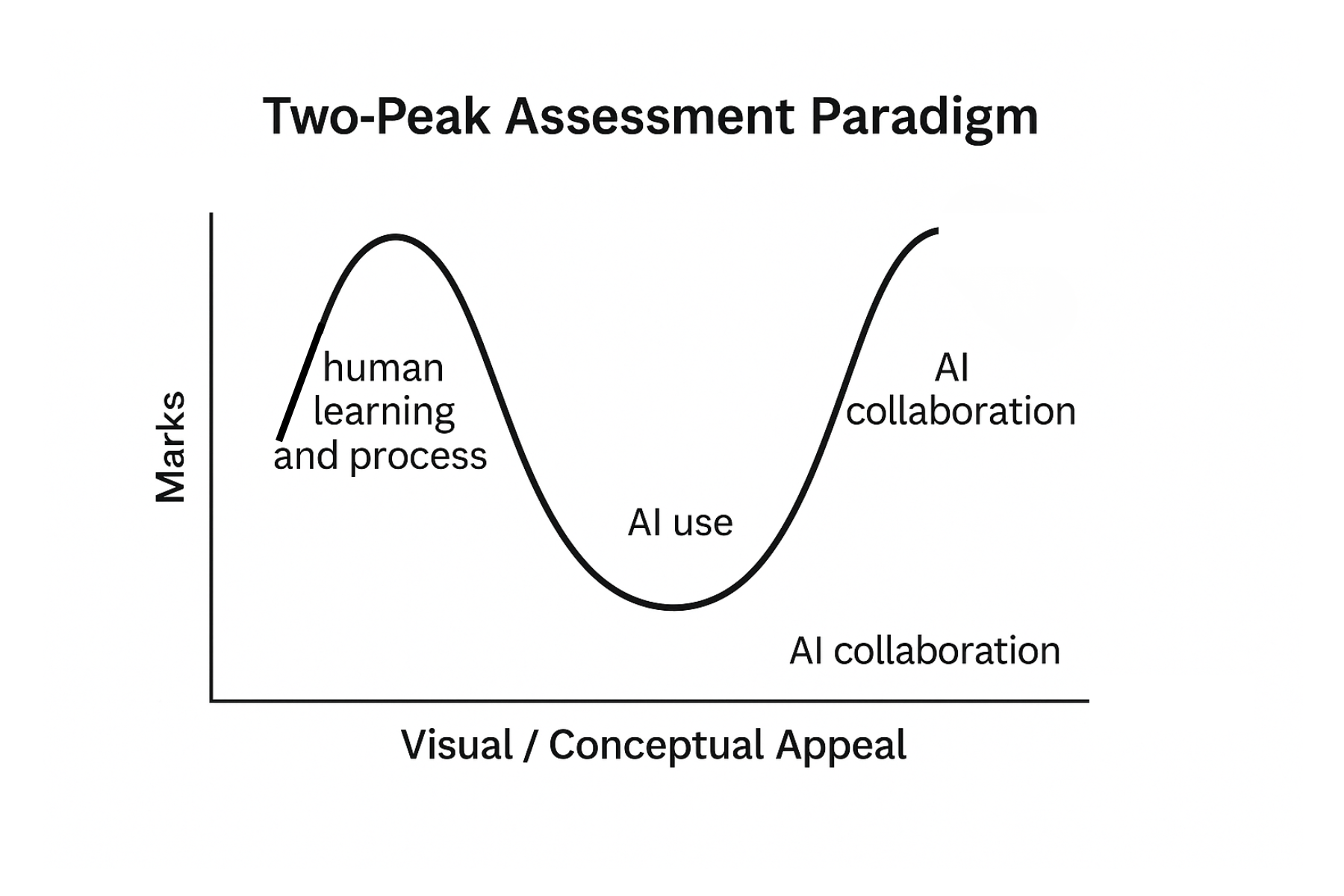

I also hope that the notoriously slow-moving systems of curriculum-development and education are focused on what strikes me as the most crucial adjustment necessary of the LLM age – assessment. Our paradigm has shifted almost instantaneously, and our previous methods of assessing work at its conclusion feel unsuited for the times we are living in. Honestly, it was never suited – but it was easier, and for the students who were able to submit a polished product thanks to the assistance of a tutor, parent, or other support, their ‘knowing’ was never assured in the time before. I hazard to say that it was our biases about who specific learners are, their backgrounds, and what they look like (plus maybe the discomfort in challenging involved families) that made us look the other way. AI didn’t break assessment — it revealed what was already broken.

While I worry that AI will mean increasingly high classroom numbers, I actually think that it calls for more teachers, more human mentorship, more conferencing and check-ins along the way – a necessity that is almost impossible in our current set-up. If AI teaches us anything, it’s that students don’t need us less — they need us differently.