Imagined as a rousing political speech, with patriotic music slowly swelling in the background.

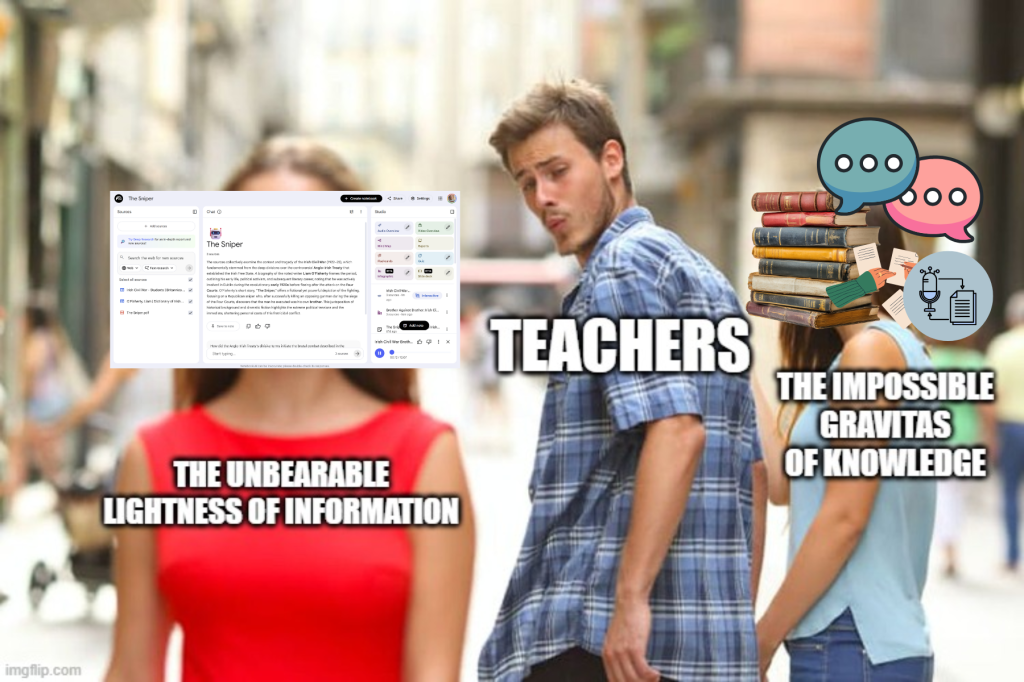

Colleagues, I know many of you are excited about NotebookLM, especially that uncannily almost-human podcast feature. We upload our readings, videos, and professional documents, then receive instant synthesis supporting multimodality and differentiated instruction. But I want us to consider what’s happening to our professional expertise when we adopt this tool—or any LLM-based assistant. We’re witnessing the remediation of educational expertise itself, transforming teachers from knowledge-holders into knowledge-brokers. NotebookLM stands out for grounding its responses in uploaded materials, lending its outputs an authority that masks their mediation.

To understand what’s at stake, let me introduce a concept from media studies: remediation. NotebookLM remediates the entire research apparatus of teaching—our file cabinets, OneDrive folders, annotated textbooks, and accumulated professional wisdom. Bolter and Grusin (2000) argue that remediation occurs through networks of formal, material, and social practices:

Formally, it remediates the academic literature review, the planning notebook, even Socratic dialogue; but promises “complete and comprehensive access to information” while obscuring the interpretive labor that transforms information into knowledge (Papacharissi, 2015).

Materially, it replaces physical artifacts of teaching expertise (marked-up curriculum guides, annotated student work, scribbles in margins) with algorithmic processes that appear transparent through source citations yet are hidden behind algorithmic choices. NotebookLM produces what Bolter and Grusin (2000) describe as hypermediacy (visible layers of mediation like source links, formats, AI voices) that paradoxically create a sense of immediacy and authority rather than critique.

Socially, it remediates us as expert practitioners. When we upload materials and receive instant analysis, our professional authority shifts from knowing to prompting—a different kind of expertise entirely.

Goodbye Inquiry, Hello Output

Linguist Adam Aleksic (2025) argues that “truly knowing an answer requires struggling with uncertainty.” Consider planning a unit on New France in Canadian history—a unit Manitoba students often struggle to find relevant. Traditionally, this required understanding primary sources, synthesizing across texts, connecting to standards, curating materials, anticipating misconceptions, designing meaningful assessment.

NotebookLM generates all of this in seconds. But as Aleksic describes, “with each additional abstraction from uncertainty, the easier it is to find answers, and the more confident those answers sound.” The tool produces seeming pedagogical expertise with the “aura of truth, objectivity, and accuracy” that danah boyd and Kate Crawford (2012) identify in Big Data mythology.

Yet can we explain why these particular connections matter? In philosophical terms: do we know what NotebookLM claims, or merely believe what it tells us?

The Question Behind the Question

Aleksic describes how “the lost ritual of asking has collapsed the meaning of the question in the first place.” When we can instantly generate unit materials, we never wrestle with fundamental questions: Why teach about New France? What should students understand? How does this connect to their lived experiences?

These aren’t questions NotebookLM can answer. They require what Haraway calls “critical, reflexive relation to our own practices” (as cited in Papacharissi, 2015). The tool can synthesize curriculum documents but cannot interrogate why we chose those documents, what we’re unconsciously prioritizing, or whose perspectives remain absent.

As Aleksic (2025) writes, “figuring out which question to ask is more important than the answer itself.” But NotebookLM’s efficiency makes all questions appear equivalent. We’re “drowning in a sea of answers, forgetting how to ask the right questions.”

Papacharissi (2015) captures this perfectly: AI outputs “oscillate between the unbearable lightness of information and the impossible gravitas of knowledge.” NotebookLM offers comprehensive information access but cannot deliver genuine pedagogical knowledge; the heavy weight of knowing that emerges only through sustained engagement with uncertainty.

Colleagues, I’m not asking us to abandon NotebookLM, but let’s use it differently. Treat its outputs as another text to interrogate, not authoritative synthesis. Our students need us to model what it means to genuinely know, not merely retrieve.

References

Aleksic, A. (2025, December 3). the importance of not knowing. Substack.com; The Etymology Nerd. https://etymology.substack.com/p/the-importance-of-not-knowing

Bolter, J. D., & Grusin, R. (2000). Remediation : Understanding new media. MIT Press.

Boyd, D., & Crawford, K. (2012). Critical questions for big data: Provocations for a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 662–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878

Papacharissi, Z. (2015). The unbearable lightness of information and the impossible gravitas of knowledge: Big Data and the makings of a digital orality. Media, Culture & Society, 37(7), 1095–1100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443715594103