a study of @etymologynerd

When I read this assignment outline, I immediately thought of @etymologynerd. Adam Aleksic’s posts are uniquely meta. He explains the history of our spoken and printed words and shows how that history is shaped by the media we use. In doing so, he invites viewers to understand how we’re shaped by language, how language shapes social media, how social media reshapes us and our language, how we shape the media itself – and how it all comes together to capture our attention. His videos use the same rhetorical hooks and algorithmic tricks that keep people scrolling, but he also exposes those mechanisms, breaking down the walls of manipulation to make them visible.

Aleksic is a Gen Z Harvard linguistics graduate. As a high school student, he started an etymology blog and became a prolific Reddit poster, learning how to game a much simpler algorithm than we face today (Peterson, 2025). After earning his BA in Linguistics, he shifted into short-form video in 2023. By 2024 many of his videos regularly surpassed one million views. Today he has over 800,000 followers on TikTok and more than one million on Instagram, where his posts often circulate beyond each platform’s walls. I first encountered his “dolphin language” series while not even using TikTok.

Although he keeps his following list small, the accounts he does follow map onto his niche interests: other linguistics educators (@linguisticdiscovery, @lingonardi), academically adjacent creators (@magic.c8.ball, @astro_alexandra), and quirky internet-culture archivists (@depthsofwikipedia). These affiliations reflect the tone that defines his work: grounded and absurd.

That blend is especially visible in the dolphin videos, which offer a helpful starting point for analysis (Fig. 1).

Bolter and Grusin (2000) define a medium as something that remediates. Or rather, it refashions the social significance and techniques of previous media forms into something new (p. 45). We see what would traditionally be a written linguistics exercise transformed into a multimodal micro-lesson and performance. The linguistic concepts in the video are remediated through absurdist humor: a parody that simultaneously entertains and instructs. It is a modern take on the joke about comma usage between the phrases ‘Let’s eat, Grandma’ and ‘Let’s eat Grandma’. Despite the absurdity, the underlying lesson remains intact: languages are built from arbitrary rules. This “theory by parody” makes complex linguistic concepts legible to a broader audience by turning exposition into performance. The humor functions pedagogically: Aleksic embodies the rule rather than explaining it. Ultimately, the clip demonstrates Bolter and Grusin’s logics of immediacy and hypermediacy. Immediacy appears in the illusion of direct communication and the sense of transparency created through voice, sound, and viewer address, while hypermediacy emerges in our constant awareness of the medium itself—through captions, editing cuts, and the dolphin-language grammar chart superimposed behind him (pp. 71, 81–82).

That being said, no one is going to watch this video and come away able to create their own conlang. This is a hook rather than a full lesson—an entry point that sparks wonder rather than mastery. It is engagement through wonder, a perfect example of affective pedagogy. The brevity and interactivity turn learning into an invitation; the comment section, duets, and follow-ups become the extended classroom. It makes linguistic systems accessible to people who might never encounter academic linguistics. In this sense, it self-remediates and thus translates scholarly explanation into algorithmically optimized curiosity. One has to wonder, to borrow from Latour’s Actor–Network Theory, how these technological prescriptions (such as brevity, performance, and engagement incentives) will ripple out into the future of learning, shaping not only how knowledge circulates but how attention itself is disciplined (Latour, 1988).

Aleksic is aware of the attentional demands placed upon him by the medium. Like many, his videos are known for their fast pace and use of an influencer accent. In his recent book Algospeak, he describes it as a form of uptalk in which there is a rising tone on a stressed syllable with continued high tones until the completion of speech. This emphasis serves to hold a viewer’s attention (Aleksic, 2025). It is speech, optimized for the algorithm.

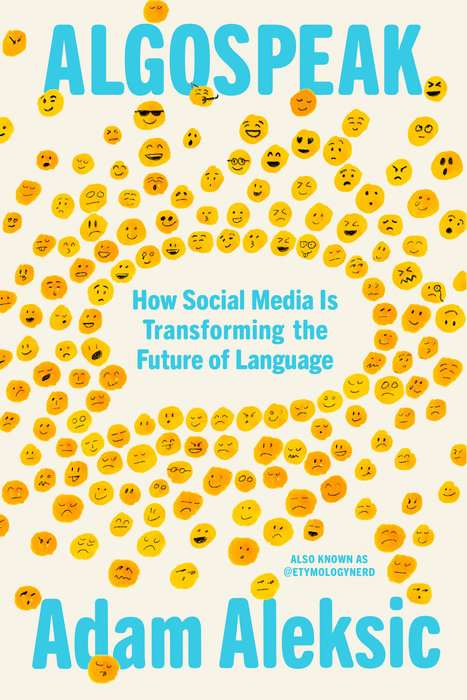

This is an example of how retention-rate metrics shape the TikTok ecosystem. In fact, “retention rate” appears on nine out of the book’s 220 pages (Aleksic, 2025, p. 242). He explicitly references his use of trending terminology as video frames because of how it impacts engagement metrics, stating that many topics interest him—but that he knows they will not bring the same viewers as trending ones. This leads to videos like the following, which harness trending brainrot and memetic terminology to introduce the concept of the use-mention distinction (Fig. 2).

Instead of choosing to focus on academic and abstract examples, @etymologynerd moves into popular and concrete spaces. The algorithm itself begins to co-author meaning: language is a performance, a signal of in-group belonging, and an object designed to optimize metrics. In this video, linguistic meaning shifts from semantic work (referring to something in the world) to social work (signaling a shared cultural context). The reference is the joke, and thus it becomes meta-communication about referencing the reference. His delivery shows his awareness of how the algorithm scripts his choices, but the content itself shows what the platform is scripting for all of us. TikTok remediates language from a communication tool into a participation badge – a way to show that you belong to the network. Educational theory becomes a theory of belonging, not just understanding.

But TikTok also dis-enables important dimensions of learning. The rapid pacing, short runtime, and endless For You scroll reward quick consumption rather than slow thinking. Reflection is costly on a platform where attention is the primary currency. Videos can be difficult to relocate later unless a viewer follows the creator, which makes deeper engagement fragile and fleeting. Misinterpretation rises when nuance is compressed into punchlines and edits.

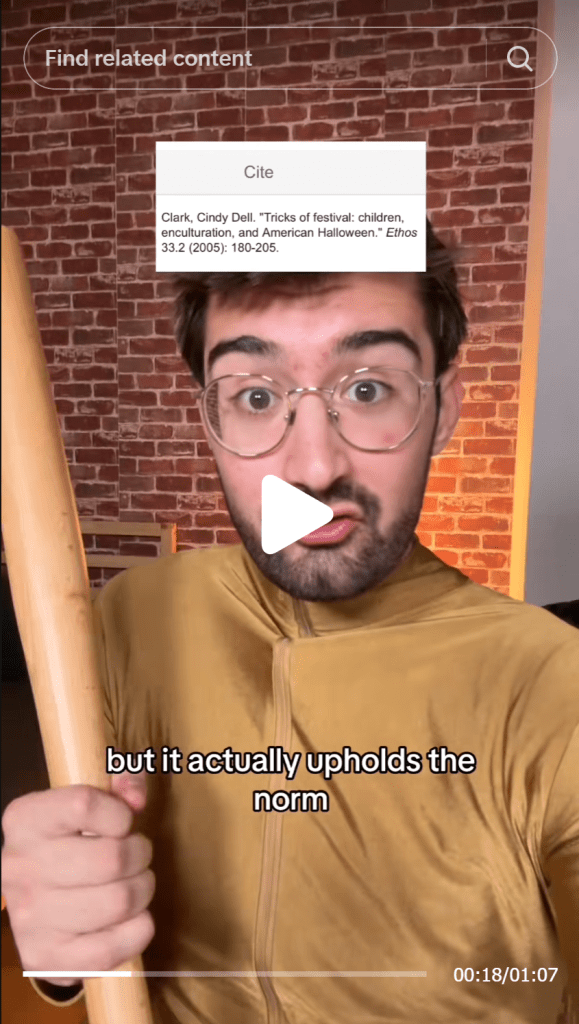

Citation (Fig. 3) poses a distinct challenge. Aleksic makes a noticeable effort to visually cite academic sources on screen, but those references disappear as quickly as they appear. They cannot be clicked, traced, or peer-verified in the moment. The platform’s ephemerality means that sources, while visible, remain challenging to verify. In this way, TikTok pushes creators to monetize attention and charisma over ideas. The medium privileges credibility-as-aesthetic over credibility-as-evidence. It also leads to potential misuse and abuse as poor-faith actors use them to build credibility.

In my estimation, as an educational tool, TikTok is mostly hook, but no line. It can lead to new understanding, and Aleksic’s work feels like a kind of harm-reduction approach to academic thinking: a way to keep deeper ideas alive within the feed. As Latour notes, technologies prescribe actions and competencies in advance, imagining a user who will behave as scripted. Yet real users often comply partially, resisting or reshaping those prescriptions. He describes how networks of aligned set-ups form what Waddington called a chreod—a necessary path that silently channels users toward the expected behavior (Latour, 1988, p. 308). TikTok’s chreod rewards speed, humor, outrage, and referential belonging. Real learners may diverge, but the medium continually nudges them back onto that narrow track of attention. To land a big fish, we need the hook of attention and the line of sustained learning. Hopefully, too much of one doesn’t destroy the other.

References

Aleksic, A. [@etymologynerd]. (2023). #conlang #language #linguistics #dolphin #harvard #greenscreen [Video]. In TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@etymologynerd/video/7544794226249321741

Aleksic, A. [@etymologynerd]. (2024). words become funny because they are words that are funny #etymology #linguistics #language #hawktuah #skibidi #philosophy #logic #semantics [Video]. In TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@etymologynerd/video/7421288562651319582

Aleksic, A. [@etymologynerd]. (2025). BOO 👻 #semiotics #culture #halloween #costume #sociology [Video]. In TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@etymologynerd/video/7562712621909019917

Aleksic, A. (2025). Algospeak. Knopf.

Bolter, J. D., & Grusin, R. (2000). Remediation : Understanding new media. MIT Press.

Johnson, J. (1988). Mixing humans and nonhumans together: The sociology of a door-closer. Social Problems, 35(3), 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.1988.35.3.03a00070

Peterson, A.H. (Host). (2025, September 10). How algorithms are changing the way that we talk [Audio podcast episode]. In Culture Study Podcast. https://podcasts.apple.com/ca/podcast/how-algorithms-are-changing-the-way-we-speak/id1718662839?i=1000725863919