it’s media all the way down

Media ecology is the study of how media and technology function as environments that shape human perception, communication, and understanding. It looks not just at content, but at the structures and systems we build and are surrounded by, from language to smartphones, and how they shape what we can think, say, and do. Like an ecosystem, these media interact with one another and with us, constantly reshaping our cultural and intellectual “habitat.” Media ecology asks the right questions because it recognizes that anything that impacts our communication or interaction provides limits and biases to what is possible. Without recognizing the impact of these impositions we risk mistaking the shape of our media environment for the shape of reality itself.

This definition aligns with Strate’s (2000, as cited in Strate and Lum, 2020) argument that media ecology is a perspective; “a way of seeing”—that treats media as environments rather than just channels. Neil Postman (as cited in Lum, 2000) similarly calls media ecology “the study of the cultural consequences of media change that affects our social organization, cognitive habits, and political ideas” (p. 4). In other words, it is not enough to examine what media say; we must examine what they make possible and what they make difficult to imagine.

Strate and Lum (2000) situate media ecology within a tradition that is ecological, interdisciplinary, and activist, drawing on Patrick Geddes’ view that intellectuals must act as shapers of environments, not just observers (p. 60). This implies that media ecology cannot belong neatly to one discipline. It is necessarily intersectional, combining insights from communication studies, history, sociology, semiotics, and philosophy. Thinking ecologically means remembering that, as Miller (1989) puts it, “no living organism can be understood except in terms of the total environment in which it functioned” (as cited in Strate & Lum, 2000, p. 68).

Mumford’s historical schema illustrates how environments structure society over time. His three phases—eotechnic, paleotechnic, and neotechnic—mark shifts from renewable energy to industrial extraction to machine-human symbiosis, with each stage reorganizing labor, power, and social classes (Strate & Lum, 2000, pp. 63–65). These phases demonstrate that technological environments are not neutral: they define the “rules of the game” for entire cultures.

Lum (2000) further explains that media have both physical and symbolic dimensions, each with distinct biases. These biases can be temporal, spatial, sensory, political, social, metaphysical, or epistemological (p. 2). To do media ecology is to surface these biases and ask what forms of knowledge, attention, and relationship they enable—and which they foreclose. This is why media ecology “asks the right questions.” It does not merely catalog media; it interrogates how each medium privileges some possibilities and silences others.

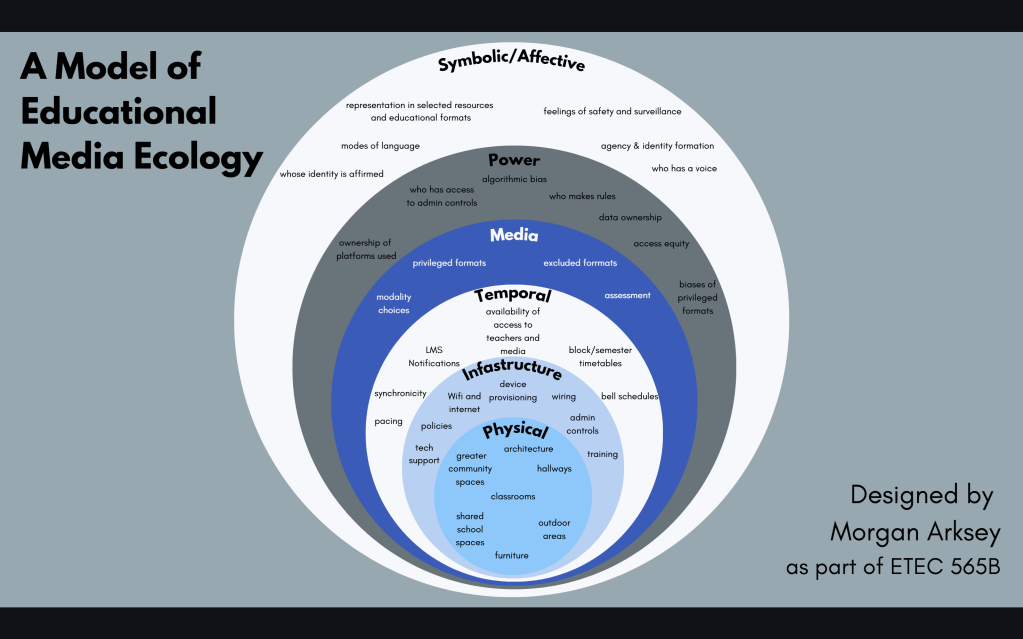

Model of Educational Media Ecology

References

Lum, C. M. K. (2000). Introduction: The intellectual roots of media ecology. New Jersey Journal of Communication, 8(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870009367375

Strate, L., & Lum, C. M. K. (2000). Lewis Mumford and the ecology of technics. New Jersey Journal of Communication, 8(1), 56–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870009367379