![A typewritten cover on orange paper.

Document is entitled "Indian Education in Manitoba; information for educaters [sic] & band officials"

The document was published by the Department of Indian Affairs and Norther Development's Manitoba Regional Office - Education Division, and was published in 1972.](https://themarksey.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/screenshot-2024-01-15-172158.png?w=230)

Preface

It is crucial to understand that marginalized populations are often constrained by the systems imposed by the dominant culture, through no fault of their own. What follows aims to offer a historical perspective on how these communities can become entangled in their own marginalization while trying to effect change from within systems that have historically excluded them or limited their access.

Original Question

What kind of information is provided in early documents about Indigenous Education in Manitoba seemingly endorsed by Indigenous groups?

Search terms

- “Indian” – as I am searching for an early document around Indigenous education in the Province of Manitoba I am restricted to using the terminology of the time period

- “Education”

- “Manitoba”

Document Source

My initial search was completed using the Government of Canada’s Publications catalogue. Using my search terms, I was able to uncover a document entitled “Indian education in Manitoba: information for educaters [sic] & band officials”, which was published in 1972 by the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs. The document starts with a 2-page letter of introduction from the Manitoba Indian Brotherhood, the forerunner of the current Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (Manitoba Historical Society Archives, 2022).

Initial Analysis

* I did not include uses of the word Indian when referring to organizations/groups like the Manitoba Indian Brotherhood or the Department of Indian Affairs, or in document titles.

* Only the main body text was analyzed, not appendices.

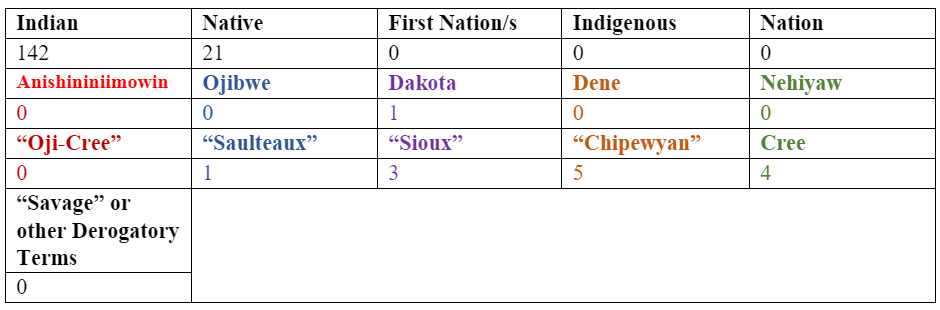

Added to the original search terms, I included the names of Indigenous Nations in the province of Manitoba, both as used by most groups themselves currently as well as historical terminology, which is recorded in quotation marks in the chart above. Interestingly, while terms used to represent the entirety of Manitoba’s Indigenous population were used well over 140 times, names specific to a cultural group were only mentioned a total of 14 times, and only in instances referring to language. Anishininiimowin (Oji-Cree) identity is completely unreferenced. Given the several times the document refers to the importance of cultural understanding (see paragraph 3 on page 107 for example) on the part of non-Indigenous peoples, this seems like a notable discrepancy. The prevalence of generalized terms over specific cultural group names suggests a broad-brush approach to Indigenous identity within the document, which contrasts with the expressed emphasis on cultural understanding. This raises questions about the depth and authenticity of the cultural awareness and sensitivity claimed in the document.

The map above shows the heterogeneous nature of the Indigenous communities within the Province of Manitoba. (MFNERC, 2015)

In my initial review of the document, several aspects stood out, particularly in light of historical context:

- References to Residential Schools: The document frequently mentions residential school facilities, detailing their amenities and procedures for enrolling Indigenous students. This is particularly striking given the traumatic legacy of these institutions in forcibly assimilating Indigenous children, a practice now widely recognized as part of Canada’s colonial history.

- Mentions of the Child Welfare System: There are notable references to the child welfare system, including contacts for agencies to be alerted if there were concerns about the welfare of Indigenous children. During this period, welfare agencies were actively involved in the removal of Indigenous children from their families for adoption into non-Indigenous homes, a practice later termed the Sixties Scoop (Sinclair & Dainard, 2021). The legacy of this system still has a residual hold on us; national Canadian data shows that over 50% of children in foster care today are Indigenous, in Manitoba that number is closer to 90% (Hobson, 2022)

The broad-brush approach to all Indigenous groups, and the references to residential schools and the child welfare system made me think about the ways in which marginalized populations are often positioned within dominant societal narratives, particularly in historical contexts. It highlights a systemic approach to managing Indigenous affairs that prioritizes assimilation and control over the preservation and respect of diverse cultural identities.

In terms of its impact on teacher professional development, I think that it was probably progressive for its time. Unfortunately, I still think that it would have reinforced stereotypes and encouraged stigmatizing and problematic behaviours from non-Indigenous readers. On one hand, historically used derogatory terminology is absent (with the notable exception of settler names for some Indigenous groups), but from a modern lens the frequent use of the term Indian is jarring. The document explains that intelligence tests cannot be removed from culture (p. L1) and gives some attention to the importance of cross-cultural training (p. C3). But ultimately, the information contained within reflects the values of the dominant Manitoban culture, and reinforces systems that continued to do significant harm to Indigenous people. Much of the document is about funding allocations, welfare concerns, and different residential school locations.

Updated Question

How does the 1972 ‘Indian education in Manitoba’ document, despite its endorsement by Indigenous organizations, fail to reflect the complexities and realities of Indigenous education and cultural practices of the time?

Analysis

The opening note from the MIB sets out goals of educational autonomy and Indigenous control of their own education, ultimately a push back against the system. The final line of Verna Kirkness’ letter stating that the document that follows “will… provide you with the information on ‘things you have always wanted to know about Indian education but were afraid to ask’” makes no qualifiers on the quality of the information, and its use of quotation marks strikes me as an indication of MIBs critical stance on the material included within. However, the rest of the document presents a systemically aligned perspective on Indigenous education. From the uncritical eyes of non-Indigenous readers, this could be seen as acceptance.

Ultimately, the document remains a product of its systemic context. Its portrayal of residential schools is notably softened, a stark contrast to the more troubling accounts that have emerged since. For example on page 36 of the document, it simply says that it became evident that it was “not desirable” to remove children from families, and speaks of the benefits of Day Schools, racially segregated schools that served to assimilate Indigenous students in conditions that were frequently abusive, staffed by unqualified and non-Indigenous teaching staff and the subject of a significant Class Action Lawsuit finalized in the year 2019 (Pind, 2023). Traditional spirituality, family organization, and cultural practices are conspicuously absent from the discussion; material which quite literally is information teachers and educators should know about Indigenous education. Furthermore, the document not only encourages but also provides the necessary contacts for readers to engage with existing child welfare systems. This guidance subtly positions Indigenous families under the scrutiny of non-Indigenous systems, reflecting a lack of recognition for their autonomy and cultural integrity.

Reflection

My interest in this topic stems not only from the importance of understanding historical context in the process of Reconciliation but also from my personal identity as a member of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community and my background in social history. Like Indigenous advocacy groups, early 2SLGBTQIA+ rights groups, such as the Mattachine Society, The Daughters of Bilitis, and ONE, Inc. in the United States, and the Gay Alliance Toward Equality in Canada, faced similar challenges as a historically marginalized population struggling to gain public acceptance. These groups often adopted a strategy of respectability politics, which included things like members being forced to adhere to the acceptable gender norms of the time to avoid being labeled as deviant. For instance, having a ‘friend’ was considered acceptable, but openly describing an intimate relationship with a same-sex partner was not, as noted by Case in 2020. This approach created a divide within the marginalized communities between those who conformed to these norms and those who either could not or chose not to do so.

If we apply a definition of ‘respectability politics’ as the way in which more privileged members of marginalized groups attempt to agree with and promote mainstream cultural norms to advance their group’s condition (Dazey, 2021) then it becomes clear that this strategy, while offering potential short-term gains in acceptance and rights, can also perpetuate long-standing inequities and internal divisions. It is from this lens that I have analyzed the following document. What becomes clear is that systemic change alone is not enough to effect true and lasting societal transformation. While changes in policy and practice are crucial, they must be accompanied by a deeper shift in societal attitudes and a genuine acknowledgement of the diversity and autonomy of marginalized groups. In the case of the document I analyzed, the focus on institutional structures like residential schools and the child welfare system, even when ostensibly endorsed by Indigenous groups, reflects a top-down approach that does little to empower these communities or respect their cultural uniqueness.

Ultimately, what I will take from my reading of this document is the critical need for direct and authentic engagement with specific Indigenous communities, rather than solely relying on broad systemic approaches. True progress hinges on listening to and learning from these communities themselves, ensuring their voices and specific cultural needs are at the forefront of any educational and policy development.

References

Canadian Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Timeline LGBTQ2S . https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/timeline/lgbtq2

Case, M. (2020, July 15). ONE: The First Gay Magazine in the United States. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/one-the-first-gay-magazine-in-the-united-states/

Dazey, M. (2021). Rethinking respectability politics. The British Journal of Sociology, 72(3), 580–593. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12810

Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. (1972). Indian education in Manitoba: Information for educators & band officials. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/aanc-inac/R44-134-1972-eng.pdf

Hobson, B. (2022, September 21). More than half the children in care are Indigenous, census data suggests. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/census-indigenous-children-care-1.6590075

Manitoba Historical Society Archives. (2022, October 26). Manitoba organization: Manitoba Indian Brotherhood / Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs. https://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/organization/assemblymanitobachiefs.shtml

MFNERC. (2015). Traditional First Nation Community Names. https://mfnerc.org/community-map/

Pind, J. (2023, August 23). Indian Day Schools in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/indian-day-schools-in-canada

Sinclair, N. J., & Dainard, S. (2021, February 17). Sixties Scoop. The Canadian Encyclopedia; The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sixties-scoop